→

Scroll to discover more

The story of Chanel No. 5

The invisible brand leader

There is one brand leader that has held its position for more than 100 years.

Unquestioned and unassailable, it outsells the competition in every market, in some cases it outsells all of the competition put together.

The product has never changed and the packaging is practically identical to the day was launched.

This is a mass-market product that still manages to glow with an aura of pure luxury.

Chanel No 5.

Unquestionably Number One. But in the depths of its story there are some surprises, some shocks, and even a very good reason why customers might feel entitled, or even obliged, to boycott the brand forever.

It’s in the nature of perfume to be mysterious, but even by the standards of the category the story of No. 5 is a maze created from smoke and mirrors. It’s a story that includes titled lovers, suites at the Ritz, war, smuggling, betrayal and the most beautiful film star in the world insisting that all she wore in bed was a few drops of Chanel No. 5.

You couldn’t make it up. Having said that, Chanel pretty much did. Most of what we think we know about No. 5 emanates from a tiny, impeccably elegant woman at 31 Rue Cambon. Not a reliable source.

An informal brand audit may direct a beam into some murky corners.

Unquestioned and unassailable, it outsells the competition in every market, in some cases it outsells all of the competition put together.

The product has never changed and the packaging is practically identical to the day was launched.

This is a mass-market product that still manages to glow with an aura of pure luxury.

Chanel No 5.

Unquestionably Number One. But in the depths of its story there are some surprises, some shocks, and even a very good reason why customers might feel entitled, or even obliged, to boycott the brand forever.

It’s in the nature of perfume to be mysterious, but even by the standards of the category the story of No. 5 is a maze created from smoke and mirrors. It’s a story that includes titled lovers, suites at the Ritz, war, smuggling, betrayal and the most beautiful film star in the world insisting that all she wore in bed was a few drops of Chanel No. 5.

You couldn’t make it up. Having said that, Chanel pretty much did. Most of what we think we know about No. 5 emanates from a tiny, impeccably elegant woman at 31 Rue Cambon. Not a reliable source.

An informal brand audit may direct a beam into some murky corners.

A Bottle of Chanel No. 5 Eau de Parfum

The product.

Any perfumier will insist on a clear brief before they start to create. In this case the brief was brilliantly clear: it was one word - Chanel.

As always, she knew exactly what she wanted. She had started thinking about perfume ten years before she produced it, in 1911. At that time her business was millinery. Her hats did well but that wasn’t important because her principal means of support was a series of aristocratic lovers. From her late teens to mid-20s she lived, perfectly openly, as a member of the demi-monde. With her boyish figure she was much in demand and moved effortlessly from one aristocratic estate to another, along the way learning how to mingle with high society and ride fast horses. For a child raised in an orphanage attached to a very severe convent this was quite a journey. But Chanel hadn’t even started yet.

In 1911 she fell in love with a wealthy, polo-playing Englishman, Arthur “Boy" Capel. He was the one. And he would remain the one - despite all of the others – until she died 60 years later. By all accounts, he felt the same. But he was duty-bound to marry the woman that his mother would choose for him, which he did 10 years after his affair with Chanel started. They continued to see one another, his marriage was no more than an inconvenience, but it ended tragically one night in 1919 when his car went off the road on the coastal route between St Raphael and Cannes. He was always fast, and champagne made him faster.

Chanel was devastated. But she was no longer the vulnerable young woman who had gone into that relationship. In 1912 Boy Capel financed her first store in Deauville where she sold her own line of sportswear made from light jersey fabric. It was an immediate success. All through the First World War she was designing clothes in jersey fabrics that were easy and practical for women to wear. By the time the war ended she was a rich and successful businesswoman with an instinct for the changing roles of women and the clothes they would need to fulfil them.

But Capel stayed in her mind, in ways that none of her other lovers would. She said he smelt of “leather, horses, forest, and saddle soap” and for years afterwards any one of these things could stop her in her tracks with tears in her eyes. She had an intense sense of smell. Raised in an environment of scrubbed wooden floors and plain stone walls, with the windows open to the forest outside, she was always acutely aware of atmosphere. Years later, when she left her apartment at the Ritz to make the chauffeur-driven trip round the corner to work, the hotel staff would phone the shop to make sure the assistants had sprayed the famous mirrored staircase with No. 5 before she arrived. This happened every day for thirty years.

In Venice, Chanel met a much younger man to whom she had been introduced in Biarritz some months earlier. He was Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, an exiled prince who was a cousin of the last czar, Nicholas the Second. They became lovers and the Grand Duke was able to introduce her to all kinds of fascinating Russian exiles.

Any perfumier will insist on a clear brief before they start to create. In this case the brief was brilliantly clear: it was one word - Chanel.

As always, she knew exactly what she wanted. She had started thinking about perfume ten years before she produced it, in 1911. At that time her business was millinery. Her hats did well but that wasn’t important because her principal means of support was a series of aristocratic lovers. From her late teens to mid-20s she lived, perfectly openly, as a member of the demi-monde. With her boyish figure she was much in demand and moved effortlessly from one aristocratic estate to another, along the way learning how to mingle with high society and ride fast horses. For a child raised in an orphanage attached to a very severe convent this was quite a journey. But Chanel hadn’t even started yet.

In 1911 she fell in love with a wealthy, polo-playing Englishman, Arthur “Boy" Capel. He was the one. And he would remain the one - despite all of the others – until she died 60 years later. By all accounts, he felt the same. But he was duty-bound to marry the woman that his mother would choose for him, which he did 10 years after his affair with Chanel started. They continued to see one another, his marriage was no more than an inconvenience, but it ended tragically one night in 1919 when his car went off the road on the coastal route between St Raphael and Cannes. He was always fast, and champagne made him faster.

Chanel was devastated. But she was no longer the vulnerable young woman who had gone into that relationship. In 1912 Boy Capel financed her first store in Deauville where she sold her own line of sportswear made from light jersey fabric. It was an immediate success. All through the First World War she was designing clothes in jersey fabrics that were easy and practical for women to wear. By the time the war ended she was a rich and successful businesswoman with an instinct for the changing roles of women and the clothes they would need to fulfil them.

But Capel stayed in her mind, in ways that none of her other lovers would. She said he smelt of “leather, horses, forest, and saddle soap” and for years afterwards any one of these things could stop her in her tracks with tears in her eyes. She had an intense sense of smell. Raised in an environment of scrubbed wooden floors and plain stone walls, with the windows open to the forest outside, she was always acutely aware of atmosphere. Years later, when she left her apartment at the Ritz to make the chauffeur-driven trip round the corner to work, the hotel staff would phone the shop to make sure the assistants had sprayed the famous mirrored staircase with No. 5 before she arrived. This happened every day for thirty years.

In Venice, Chanel met a much younger man to whom she had been introduced in Biarritz some months earlier. He was Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, an exiled prince who was a cousin of the last czar, Nicholas the Second. They became lovers and the Grand Duke was able to introduce her to all kinds of fascinating Russian exiles.

Coco Chanel

And here is one of the great mysteries about Chanel. She wasn’t pretty in any conventional sense (The three classic portraits - by Man Ray, Horst and Lipnitski – all angled her to profile and propped her distractingly with ropes of pearls and a cigarette.) and she certainly didn’t have a classically feminine figure. Yet everyone who met her came away with impression that she was beautiful. She was her own creation. Unforgettable. Every woman in the room turned as she went by.

The Grand Duke introduced her to the mysteries of Russian perfumes. Today French perfume is assumed to be the finest. Before 1917, it was all about Russian. But Comrade Lenin was, by all accounts, not a fellow to waste much water on personal hygiene far less pollute himself with bourgeois fragrances: if you want to set the world on fire it doesn’t matter what you smell like. And so the finest perfumiers in the world ended up working as waiters in Paris.

The French perfume industry were taking full advantage of this influx of expertise. François Coty, a descendant of Napoleon, had made a fortune by establishing the brand that we still know today. The Russians were allowing him to take his business to unimaginable heights.

The Grand Duke introduced her to the mysteries of Russian perfumes. Today French perfume is assumed to be the finest. Before 1917, it was all about Russian. But Comrade Lenin was, by all accounts, not a fellow to waste much water on personal hygiene far less pollute himself with bourgeois fragrances: if you want to set the world on fire it doesn’t matter what you smell like. And so the finest perfumiers in the world ended up working as waiters in Paris.

The French perfume industry were taking full advantage of this influx of expertise. François Coty, a descendant of Napoleon, had made a fortune by establishing the brand that we still know today. The Russians were allowing him to take his business to unimaginable heights.

Marilyn Monroe putting on Chanel No. 5 Eau de Parfum

The place.

The Grand Duke took Chanel to Grasse, where she found the finest lavender in Europe. The same lavender that's still used today in Number 5.

But Chanel famously said “A woman should not smell like a flower, she should smell like a woman.” She wanted a scent in two layers. A clean fresh surface then something much darker and more seductive underneath. “Like a lover’s bedsheets”. Forty years later Marilyn Monroe unconsciously echoed that sentiment when she whispered that all she wore in bed was a few drops.

The Grand Duke took Chanel to Grasse, where she found the finest lavender in Europe. The same lavender that's still used today in Number 5.

But Chanel famously said “A woman should not smell like a flower, she should smell like a woman.” She wanted a scent in two layers. A clean fresh surface then something much darker and more seductive underneath. “Like a lover’s bedsheets”. Forty years later Marilyn Monroe unconsciously echoed that sentiment when she whispered that all she wore in bed was a few drops.

A bottle of Chanel No. 5

The packaging.

Chanel was famous. The great Parisian glassware companies, Lalique and Baccarat, were confidently preparing for the task of delivering their very finest and most ornate designs for the new Chanel fragrance. But she didn’t call. In the testing rooms in Grasse she had seen the fragrances delivered in plain square bottles. As a designer she had made her reputation by simplifying womenswear, tearing away unnecessary and restricting decorations and reducing the whole outfit to a simple, beautiful, silhouette. She instinctively applied the same thinking to her bottle and in so doing created a timeless classic that has never been equalled or surpassed. Her taste was flawless.

However, if the bottle didn’t need any embellishing the story of its creation sometimes did. Chanel was known to hint vaguely that the great Cubist painter Georges Braque might have been involved in its design. He wasn’t. She could of course have chosen Pablo Picasso, who would have blithely accepted credit for any success, but she didn’t like or trust Picasso. Too similar.

The stopper is cut in the shape of Place Vendome, a favourite square. “Where I would eat a sandwich, if I were ever to eat a sandwich.”

The type was handmade, the font is not available.

Chanel was famous. The great Parisian glassware companies, Lalique and Baccarat, were confidently preparing for the task of delivering their very finest and most ornate designs for the new Chanel fragrance. But she didn’t call. In the testing rooms in Grasse she had seen the fragrances delivered in plain square bottles. As a designer she had made her reputation by simplifying womenswear, tearing away unnecessary and restricting decorations and reducing the whole outfit to a simple, beautiful, silhouette. She instinctively applied the same thinking to her bottle and in so doing created a timeless classic that has never been equalled or surpassed. Her taste was flawless.

However, if the bottle didn’t need any embellishing the story of its creation sometimes did. Chanel was known to hint vaguely that the great Cubist painter Georges Braque might have been involved in its design. He wasn’t. She could of course have chosen Pablo Picasso, who would have blithely accepted credit for any success, but she didn’t like or trust Picasso. Too similar.

The stopper is cut in the shape of Place Vendome, a favourite square. “Where I would eat a sandwich, if I were ever to eat a sandwich.”

The type was handmade, the font is not available.

“A woman should not smell like a flower, she should smell like a woman.”

The name.

There are so many stories around this name, a number circulated by Chanel herself. The most commonly heard of these, and the one used all the films, is that Chanel tested a range of fragrances and then chose the one that was number five.

The truth is more complicated and more mysterious. All her life Chanel was profoundly superstitious. The number five had particular significance for her: in her convent upbringing it played a significant role in rituals, it is vital in Theosophism – a mystical system involving seances that was very fashionable and that she took very seriously – and a fortune-teller once told her that the number five would be very significant in her life.

She always presented her dress collections on the 5th of May, the fifth month of the year.

(There is a story, no more than a rumour, that Ernest Beaux, the perfumier who created the fragrances and was a suave operator who had managed to thrive in the Czarist courts, had read his client well and ensured that the fragrance he wanted her to choose was the fifth to be presented. But that secret, were it to be true, was buried with the man.)

There are so many stories around this name, a number circulated by Chanel herself. The most commonly heard of these, and the one used all the films, is that Chanel tested a range of fragrances and then chose the one that was number five.

The truth is more complicated and more mysterious. All her life Chanel was profoundly superstitious. The number five had particular significance for her: in her convent upbringing it played a significant role in rituals, it is vital in Theosophism – a mystical system involving seances that was very fashionable and that she took very seriously – and a fortune-teller once told her that the number five would be very significant in her life.

She always presented her dress collections on the 5th of May, the fifth month of the year.

(There is a story, no more than a rumour, that Ernest Beaux, the perfumier who created the fragrances and was a suave operator who had managed to thrive in the Czarist courts, had read his client well and ensured that the fragrance he wanted her to choose was the fifth to be presented. But that secret, were it to be true, was buried with the man.)

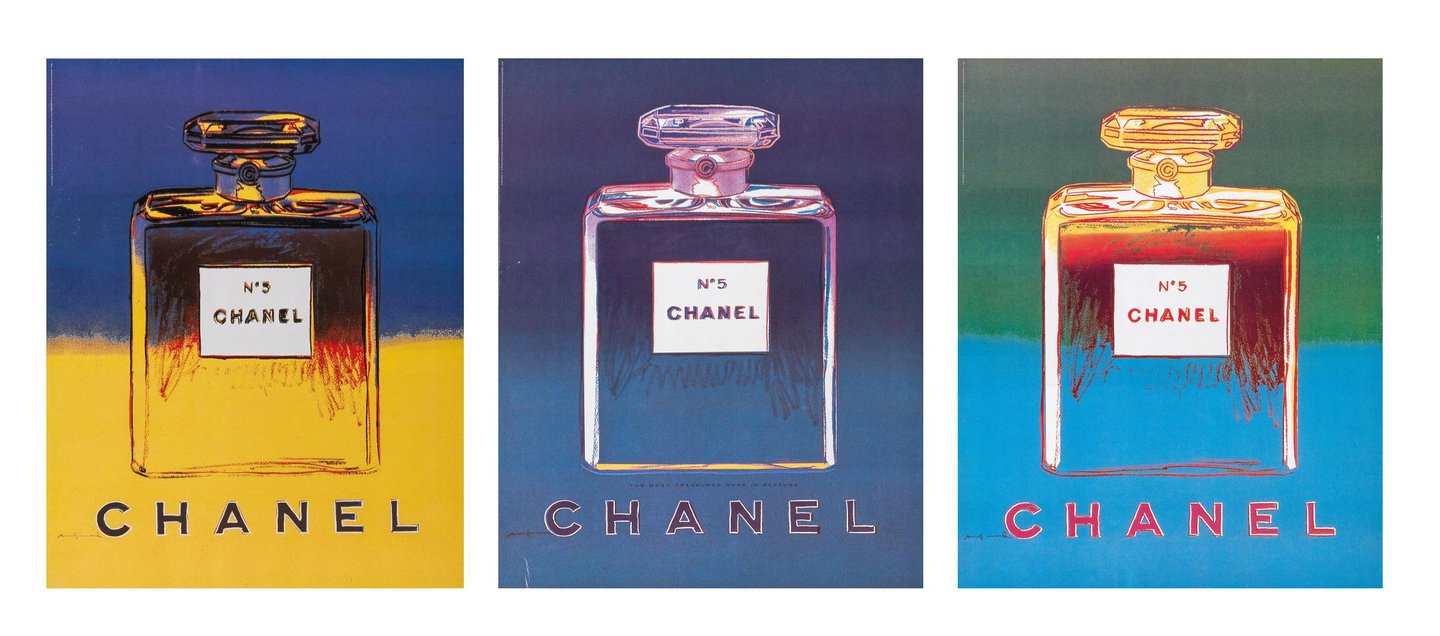

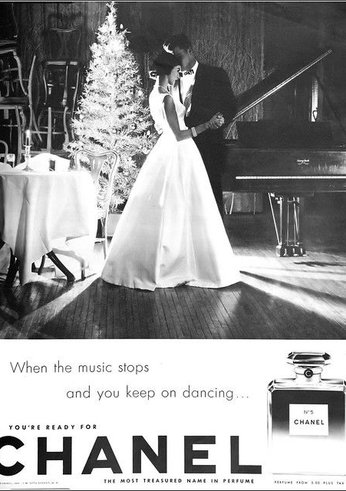

Various advertisements for Chanel No. 5

Marketing.

Chanel knew nothing of classical marketing. She was operating at a time when it was believed that the luxury brands played by rules of their own and that anything that would work for mainstream brands would be simply irrelevant in this rarified atmosphere. But she knew her audience, quite literally knew them – they were a group that she had consciously recruited and created.

She started by spraying No. 5 above her table at a fashionable restaurant in Cannes. People noticed and stopped to comment on the scent. Everything Chanel did was closely followed. Having started a rumour, she then produced the first hundred bottles and gave them as unlabelled gifts to her favoured customers. It was a prototype of influencer marketing, a century before the internet.

When the real bottles appeared in the showroom, they sold out instantly. She had launched without advertising and it would be decades before any ads were to appear.

No. 5 was an instant success. The two-tone layering of the fragrance, which Chanel described as “clean sheets and warm bodies” was something new. It gave the perfume extraordinary versatility, so it could be worn all day and into the evening. The little black dress of scents.

The 30s were a very successful time for Chanel. Her fashion business was the sensation of the time, so much so that Sam Goldwyn wrote her a contract for $1 million a year ($75 million today) to come to Hollywood for two visits each year and design costumes for his movies. She was the most famous designer in the world.

In her private life the young Grand Duke had been yanked back into respectable matrimony by his indignant mother. Chanel responded by moving into another suite at the Ritz with the Duke of Westminster. Winston Churchill was a frequent visitor. It must’ve been a rare relief for him to spend time with a hostess who smoked more than he did. (The Ritz Hotel, who kept her art deco silver cigarette boxes topped up, reckoned they needed three packs a day. And she was only there in the morning and late evenings. She did her real smoking at work.)

But Chanel quickly became bored with her fragrance. Once you’ve done it, it’s done. As far as she was concerned just putting it on the shelf to sell was not very interesting. Although it was making her a huge amount of money, she really couldn’t be bothered.

Chanel knew nothing of classical marketing. She was operating at a time when it was believed that the luxury brands played by rules of their own and that anything that would work for mainstream brands would be simply irrelevant in this rarified atmosphere. But she knew her audience, quite literally knew them – they were a group that she had consciously recruited and created.

She started by spraying No. 5 above her table at a fashionable restaurant in Cannes. People noticed and stopped to comment on the scent. Everything Chanel did was closely followed. Having started a rumour, she then produced the first hundred bottles and gave them as unlabelled gifts to her favoured customers. It was a prototype of influencer marketing, a century before the internet.

When the real bottles appeared in the showroom, they sold out instantly. She had launched without advertising and it would be decades before any ads were to appear.

No. 5 was an instant success. The two-tone layering of the fragrance, which Chanel described as “clean sheets and warm bodies” was something new. It gave the perfume extraordinary versatility, so it could be worn all day and into the evening. The little black dress of scents.

The 30s were a very successful time for Chanel. Her fashion business was the sensation of the time, so much so that Sam Goldwyn wrote her a contract for $1 million a year ($75 million today) to come to Hollywood for two visits each year and design costumes for his movies. She was the most famous designer in the world.

In her private life the young Grand Duke had been yanked back into respectable matrimony by his indignant mother. Chanel responded by moving into another suite at the Ritz with the Duke of Westminster. Winston Churchill was a frequent visitor. It must’ve been a rare relief for him to spend time with a hostess who smoked more than he did. (The Ritz Hotel, who kept her art deco silver cigarette boxes topped up, reckoned they needed three packs a day. And she was only there in the morning and late evenings. She did her real smoking at work.)

But Chanel quickly became bored with her fragrance. Once you’ve done it, it’s done. As far as she was concerned just putting it on the shelf to sell was not very interesting. Although it was making her a huge amount of money, she really couldn’t be bothered.

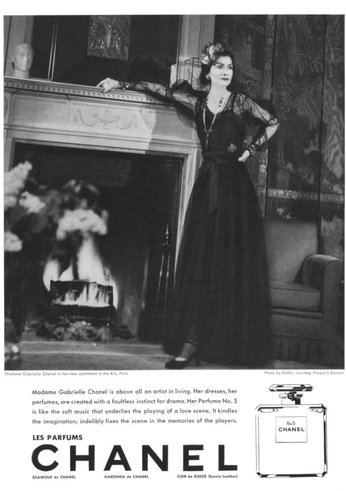

Coco Chanel adjusting a dress on a model

So, she made a momentous decision. She went into partnership with Paul and Pierre Wertheimer. The brothers’ firm, Bourjois, sold theatrical make up for vaudeville performers. Over a solitary late night cigarette Chanel may have had a frisson about cultural friction, but if she did, she didn’t say, and so the unlikely new partners held hands and jumped.

Then came the war. The Wertheimer brothers took refuge in New York and set about making Number 5 the only French perfume that mattered in America. In this they were such a success that they very quickly hit supply problems. The essential ingredient, a unique strain of lavender that was grown by the Mul family in Grasse, could not be substituted. Each bottle uses more than one thousand flowers. The answer was to send an agent in with two empty suitcases and have him smuggle the lavender essence out of the country. This they did. (The Muls have worked these fields since 1840. They still do today, and every bud they grow goes to Chanel).

Chanel Number 5 soon was, by a very long way, the best-selling perfume in America. But that was not enough for Chanel. She was horrified that her brand was being sold in drugstores. And she wanted it back. She tried every legal manoeuvre she could to force the brothers to sell her fragrance business back. When all of this failed, she resorted to a manoeuvre that is still shocking today. One that even her most ardent apologists find impossible to excuse.

She reported her Jewish partners to the Nazis.

It wasn’t hard for her to do this, as by this time she had moved into yet another suite at the Ritz with an elegant gentleman called Hans Gunther von Dinklage, who looked very dapper in his imposing dove-grey uniform (Thank you, Hugo Boss).

With the Wertheimers safely in the US, what could she possibly gain by doing that? Well, everything. It was against the law for Jews to own companies in Nazi-occupied territories. If Chanel could get the courts to agree that their shareholding was illegal then everything would revert to her.

But, thankfully, there was a flaw in the plot. The Nazis liked to see themselves as a powerful, efficient machine driven by clear-eyed idealists. Not so. Populist demagogues do not attract the fanciest of followers. Like any other such organisation, the Nazi state was infested with second-rate wide boys, thieves and conmen. Lowlifes who couldn’t make it in the straight world and were just out for what they could get. This corruption went right to the top. When Heinrich Himmler visited one of the camps he brought his wife back a new fur coat. She complained it smelled of smoke.

The Wertheimers understood the squalid reality of this seedy regime all too well. So, when the case came to court Chanel was astonished – and, comically, outraged –to discover that all of the Wertheimers paperwork was in order. They could prove that the transaction had been completed long before the Nazi occupation. It was all signed and notarised and stamped. Chanel was beside herself with outrage and indignation. She knew the papers had been backdated and that the brothers must have had under-the-counter assistance by some petty official to make sure that all the stamps were in order.

Then came the war. The Wertheimer brothers took refuge in New York and set about making Number 5 the only French perfume that mattered in America. In this they were such a success that they very quickly hit supply problems. The essential ingredient, a unique strain of lavender that was grown by the Mul family in Grasse, could not be substituted. Each bottle uses more than one thousand flowers. The answer was to send an agent in with two empty suitcases and have him smuggle the lavender essence out of the country. This they did. (The Muls have worked these fields since 1840. They still do today, and every bud they grow goes to Chanel).

Chanel Number 5 soon was, by a very long way, the best-selling perfume in America. But that was not enough for Chanel. She was horrified that her brand was being sold in drugstores. And she wanted it back. She tried every legal manoeuvre she could to force the brothers to sell her fragrance business back. When all of this failed, she resorted to a manoeuvre that is still shocking today. One that even her most ardent apologists find impossible to excuse.

She reported her Jewish partners to the Nazis.

It wasn’t hard for her to do this, as by this time she had moved into yet another suite at the Ritz with an elegant gentleman called Hans Gunther von Dinklage, who looked very dapper in his imposing dove-grey uniform (Thank you, Hugo Boss).

With the Wertheimers safely in the US, what could she possibly gain by doing that? Well, everything. It was against the law for Jews to own companies in Nazi-occupied territories. If Chanel could get the courts to agree that their shareholding was illegal then everything would revert to her.

But, thankfully, there was a flaw in the plot. The Nazis liked to see themselves as a powerful, efficient machine driven by clear-eyed idealists. Not so. Populist demagogues do not attract the fanciest of followers. Like any other such organisation, the Nazi state was infested with second-rate wide boys, thieves and conmen. Lowlifes who couldn’t make it in the straight world and were just out for what they could get. This corruption went right to the top. When Heinrich Himmler visited one of the camps he brought his wife back a new fur coat. She complained it smelled of smoke.

The Wertheimers understood the squalid reality of this seedy regime all too well. So, when the case came to court Chanel was astonished – and, comically, outraged –to discover that all of the Wertheimers paperwork was in order. They could prove that the transaction had been completed long before the Nazi occupation. It was all signed and notarised and stamped. Chanel was beside herself with outrage and indignation. She knew the papers had been backdated and that the brothers must have had under-the-counter assistance by some petty official to make sure that all the stamps were in order.

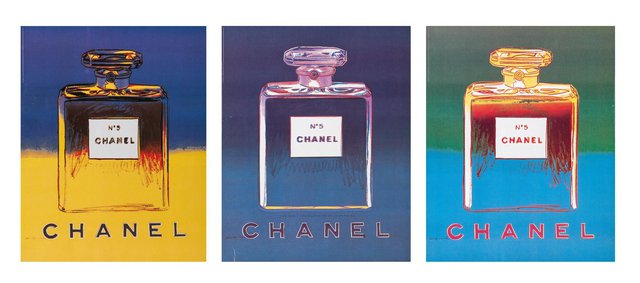

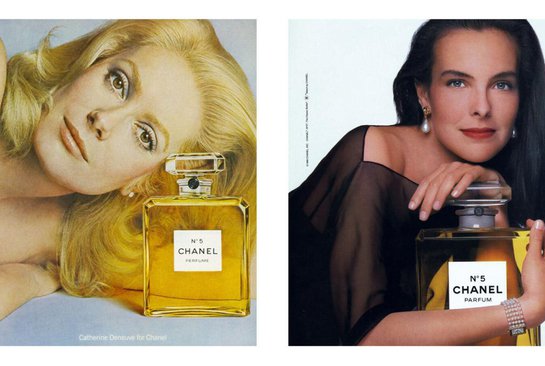

Some previous faces of Chanel No. 5

But there was nothing she could do. For the next five years she made everyone’s life as miserable as possible by launching lookalike brands and implying at every possible opportunity that the Number 5 that you’re buying today is nothing like the original she created all these years ago.

But no one was listening. They had other things on their minds. The brand went from strength to strength. It was a time when people wanted the reassurance of things that they could believe in, and they could believe in the magic of Number 5.

As soon as it was safe, the Wertheimers returned to Paris. They are a bright light in this murky tale, because from then on they behaved honourably and with more decency than most of us would be capable of. They reinstated Chanel’s shares in the company and backdated all the payments that were due to her but that could not be made in wartime. And then they went further in helping to re-establish her reputation by financing her business and assisting her to return from Switzerland where she had prudently found refuge at the end of the war.

Chanel re-established herself as the finest couturier in Paris, whilst the fragrance that bore her name sailed serenely on.

As indeed it did.

The graph is a graceful upward swoop with the exception of one deep blip in the 60s when, in common with most luxury brands, Chanel found itself out of step with the times. No. 5 had been too successful and had become overexposed, to the extent of being sold in discount drugstores. Precisely what Madame had predicted all these years ago. For the first time a proper advertising agency was appointed and real attention was paid to the marketing of this unique product.

No. 5 was the first perfume brand to produce television commercials (in so doing raising the curtain on a genre of advertising where less assured practitioners regularly stumble from the poetic to the preposterous. If you have nothing to say the best way to say it is in film.)

Films need faces. To be the face of Chanel No. 5 became an honour in itself. The tradition was started with Catherine Deneuve, through Nicole Kidman directed by Baz Luhrmann, to Marion Cotillard.

But no one was listening. They had other things on their minds. The brand went from strength to strength. It was a time when people wanted the reassurance of things that they could believe in, and they could believe in the magic of Number 5.

As soon as it was safe, the Wertheimers returned to Paris. They are a bright light in this murky tale, because from then on they behaved honourably and with more decency than most of us would be capable of. They reinstated Chanel’s shares in the company and backdated all the payments that were due to her but that could not be made in wartime. And then they went further in helping to re-establish her reputation by financing her business and assisting her to return from Switzerland where she had prudently found refuge at the end of the war.

Chanel re-established herself as the finest couturier in Paris, whilst the fragrance that bore her name sailed serenely on.

As indeed it did.

The graph is a graceful upward swoop with the exception of one deep blip in the 60s when, in common with most luxury brands, Chanel found itself out of step with the times. No. 5 had been too successful and had become overexposed, to the extent of being sold in discount drugstores. Precisely what Madame had predicted all these years ago. For the first time a proper advertising agency was appointed and real attention was paid to the marketing of this unique product.

No. 5 was the first perfume brand to produce television commercials (in so doing raising the curtain on a genre of advertising where less assured practitioners regularly stumble from the poetic to the preposterous. If you have nothing to say the best way to say it is in film.)

Films need faces. To be the face of Chanel No. 5 became an honour in itself. The tradition was started with Catherine Deneuve, through Nicole Kidman directed by Baz Luhrmann, to Marion Cotillard.

Marion Cotillard for Chanel No. 5

History has been written by men, so it’s hardly surprising that history is about men. As a result, Chanel is often seen as something of a footnote – OK she was successful, but she was a woman in the fashion business, which isn’t really a business at all, is it? No it’s not, it’s a huge global enterprise which is valued at more than $14 billion today. Had she been a man, she would be acknowledged as a titan.

More than any other designer she changed the way that women wore clothes. She threw away corsets and redundant bits of decoration and left light, simple, flowing lines in modern fabrics. Her clothes were sporty before that was a word. Elsa Schiaparelli was flashy, Hubert de Givency was luxe, but Chanel was wearable.

What is really astonishing is that she did it all alone. Absolutely alone. There were no partners, no boards, no advisors. No collaborators. Every single decision was a Chanel decision. She was a combination of Jobs, Wozniak and Ives. She spent every day in the workshop making the products that the company sold. She designed everything, from the clothes that came down the legendary mirrored staircase to the logo over the door. And, yes, even the scent that hung in the air.

On January 9, 1971 Coco Chanel was 87 years old. It was a Saturday and she spent the afternoon in her workshop checking the buttons for her new collection. As usual, she rejected more than she accepted. Then her car took her the short distance to the Ritz hotel where, the next day, Sunday, she quietly passed away. She died as she had lived, alone.

The few mourners who were allowed to visit were surprised to find Chanel in a small, simply furnished room. They had expected a grand, chandeliered suite. She had lived a life of unimaginable luxury with yachts and limousines and palaces and villas and mansions in the smartest streets in the world. In the end, the woman who had everything wanted nothing. She was back where she started. Except now she was the greatest of them all. And she knew it. What more did she need?

She made her name magical. It comes with an aura. It's impossible to say it without sighing. It almost has its own fragrance, a scent of luxury and longing.

If she had done nothing else in her life, the revenue from Chanel No. 5 alone would have made Gabrielle Chanel the richest self-made woman in the world.

Paul Cardwell, The Laughing Saboteur

More than any other designer she changed the way that women wore clothes. She threw away corsets and redundant bits of decoration and left light, simple, flowing lines in modern fabrics. Her clothes were sporty before that was a word. Elsa Schiaparelli was flashy, Hubert de Givency was luxe, but Chanel was wearable.

What is really astonishing is that she did it all alone. Absolutely alone. There were no partners, no boards, no advisors. No collaborators. Every single decision was a Chanel decision. She was a combination of Jobs, Wozniak and Ives. She spent every day in the workshop making the products that the company sold. She designed everything, from the clothes that came down the legendary mirrored staircase to the logo over the door. And, yes, even the scent that hung in the air.

On January 9, 1971 Coco Chanel was 87 years old. It was a Saturday and she spent the afternoon in her workshop checking the buttons for her new collection. As usual, she rejected more than she accepted. Then her car took her the short distance to the Ritz hotel where, the next day, Sunday, she quietly passed away. She died as she had lived, alone.

The few mourners who were allowed to visit were surprised to find Chanel in a small, simply furnished room. They had expected a grand, chandeliered suite. She had lived a life of unimaginable luxury with yachts and limousines and palaces and villas and mansions in the smartest streets in the world. In the end, the woman who had everything wanted nothing. She was back where she started. Except now she was the greatest of them all. And she knew it. What more did she need?

She made her name magical. It comes with an aura. It's impossible to say it without sighing. It almost has its own fragrance, a scent of luxury and longing.

If she had done nothing else in her life, the revenue from Chanel No. 5 alone would have made Gabrielle Chanel the richest self-made woman in the world.

Paul Cardwell, The Laughing Saboteur

“Perfume is an invisible piece of clothing.”

Featured stories

See all of our stories