→

Scroll to discover more

The story of Patagonia

"Our branding efforts are simple: tell people who we are"

“I’ve been a businessman for almost 60 years. It is as difficult for me to say these words as it is for someone to admit being an alcoholic or a lawyer.”

It’s the most provocative opening statement ever written in a book about business.

And it goes on:

"I’ve never respected the profession. Business has to take the majority of the blame for being the enemy of nature, for destroying native cultures, for taking from the poor and giving to the rich, and poisoning the earth with the effluent from its factories.”

These are not just the outpourings of some self-promoting “provocateur”. The author means every single word and, as we shall see, has been willing to put his money where his mouth is. A lot of money. A couple of billion dollars.

It’s the most provocative opening statement ever written in a book about business.

And it goes on:

"I’ve never respected the profession. Business has to take the majority of the blame for being the enemy of nature, for destroying native cultures, for taking from the poor and giving to the rich, and poisoning the earth with the effluent from its factories.”

These are not just the outpourings of some self-promoting “provocateur”. The author means every single word and, as we shall see, has been willing to put his money where his mouth is. A lot of money. A couple of billion dollars.

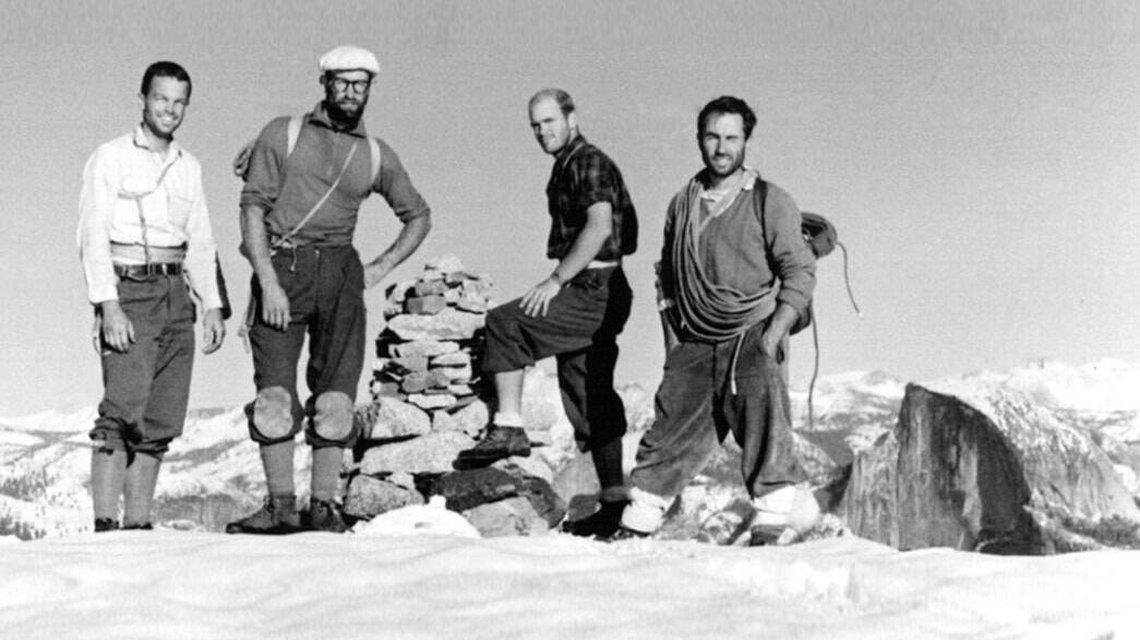

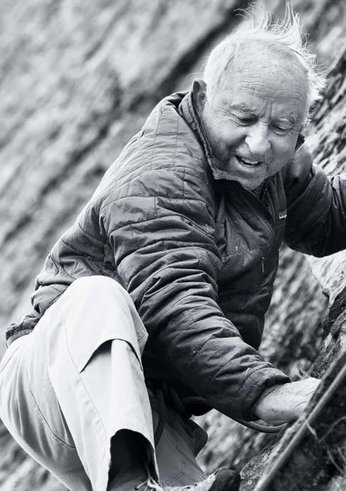

An early summit. The first of many.

Great brands are built by great personalities. These people become legends. But how many of these icons really stand up to close scrutiny. Behind every Henry Ford, Steve Jobs or Coco Chanel there are dark stories of abusive relationships, negligent parenting and workplace bullying. Could there ever, we are tempted to ask, be a successful business person who lives up to the ethical standards that we expect today?

Those who know about such things would say that Yvon Chouinard is that person and Patagonia is that brand.

So, how did it happen? How did a man who had absolutely no interest in clothes, and who never developed much interest in clothes, manage to build the most respected clothing brand in the world and then give it all away?

Because there is no doubt about the respect that Patagonia commands. For those who wear it, it’s almost a cult. And once you look into it, you’re forced to admit that they have a point. If every company behaved like Patagonia the world would be a safer, cleaner, better place. It might even have a future.

But, again, how did it happen? Yvon Chouinard didn’t spend his schooldays dreaming of fashion. He gazed out of the window and dreamt of the mountains, which were where his heart belonged. He didn’t care, and never learned to care, what he wore. A pair of jeans could last him 20 years. He wore them until they fell apart. The first repairs were patches, then, when there was nothing left to patch, he used tape.

Those who know about such things would say that Yvon Chouinard is that person and Patagonia is that brand.

So, how did it happen? How did a man who had absolutely no interest in clothes, and who never developed much interest in clothes, manage to build the most respected clothing brand in the world and then give it all away?

Because there is no doubt about the respect that Patagonia commands. For those who wear it, it’s almost a cult. And once you look into it, you’re forced to admit that they have a point. If every company behaved like Patagonia the world would be a safer, cleaner, better place. It might even have a future.

But, again, how did it happen? Yvon Chouinard didn’t spend his schooldays dreaming of fashion. He gazed out of the window and dreamt of the mountains, which were where his heart belonged. He didn’t care, and never learned to care, what he wore. A pair of jeans could last him 20 years. He wore them until they fell apart. The first repairs were patches, then, when there was nothing left to patch, he used tape.

Homeward bound...

Slip slidin’ away...

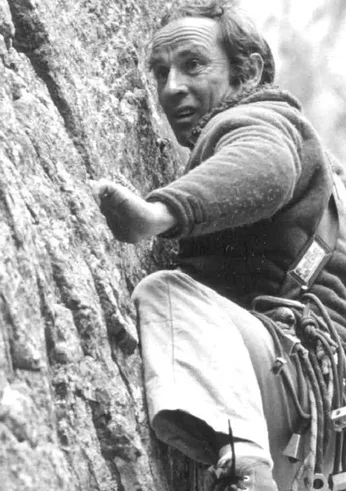

Still crazy after all these years...

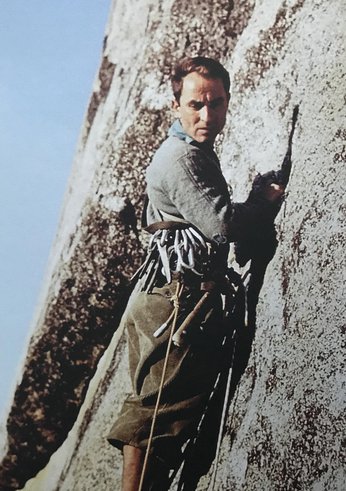

Chouinard is a rock climber, a demanding sport that’s hard on skin and the cloth that covers skin. But even amongst rockers he was known for his dirtbag style. If you’re in a store and you’re looking at jeans where the knees are fashionably ripped and frayed and the backside looks like you slid down a scree slope, you’re shelling out money to get the look that generations of climbers and surfers got the hard way. On the beach and on the boulders you don’t wear new. That would be like parting your hair.

So, as you lean back in your Uber and admire your distressed designer wear, could it be that your heart is telling you it would rather be with the wild people in the wild places?

There is a story told, and it’s probably true, that, when the Patagonia brand first became a thing, Yvon was invited to speak at a great university. An intern with a cut-glass accent called to politely remind him it was black tie. His wife, Malinda, laughed aloud when she took the call: Yvon has never, ever, owned a tie, of any colour. “He doesn’t dress up. Truth to tell, it would be pretty hard to dress him down. When he’s not in the blacksmith shop he’s surfing or climbing. And these things don’t have a dress code. I’ll get him to you and I’ll make sure he’s clean. But I can’t promise tidy.”

So, as you lean back in your Uber and admire your distressed designer wear, could it be that your heart is telling you it would rather be with the wild people in the wild places?

There is a story told, and it’s probably true, that, when the Patagonia brand first became a thing, Yvon was invited to speak at a great university. An intern with a cut-glass accent called to politely remind him it was black tie. His wife, Malinda, laughed aloud when she took the call: Yvon has never, ever, owned a tie, of any colour. “He doesn’t dress up. Truth to tell, it would be pretty hard to dress him down. When he’s not in the blacksmith shop he’s surfing or climbing. And these things don’t have a dress code. I’ll get him to you and I’ll make sure he’s clean. But I can’t promise tidy.”

If you can’t buy it, make it.

The Patagonia/Chouinard saga isn’t like a formal story. There wasn’t an author. There wasn’t a plan. Like a path through the wild, one thing followed another because it was the natural thing to do. The only way to read it is chronologically. So, let’s start at the beginning.

Education. Nothing to see here, folks. No gold stars. No stars at all. The trouble was, every classroom had a window, and everything Yvon wanted to learn was out there, not in here.

The Army, conscription, was more of the same. It had more fun to offer, but if you refuse to accept the idea of saluting there’s a limit to how far you can go.

So, out. 1964. After all that education, Yvon needed to breathe some clean air. With three friends he headed to Yosemite and, with no money and bare-bones gear, they made the first ever ten-day ascent of the North Wall on El Capitan. (A ten-day ascent means nine nights sleeping tied to the Wall. And it’s called the Wall because, well, Google it.)

He loved to rough it. In his 20s he was spending 200 nights a year sleeping out in his old ex-Army sleeping bag. “You don’t hurt it much by sleeping in it.” (He was past 40 when he first bought a tent). When the money ran out, he famously lived off dented tins of cat food that the stores couldn’t sell, supplemented with forage. Porcupine was often the dish of the day.

His first business was making and selling climbing gear. He taught himself blacksmithing from a book. Then he would salvage huge, high quality steel blades from abandoned farm machinery and drop forge them into pitons that were lighter and stronger than anything you could buy in a store.

As a blacksmith, Chouinard practised Zen: it’s possible to add by taking away. “Where other designers would work to improve the tool’s performance by adding on, we would achieve the same ends by reducing weight and bulk without sacrificing strength or the level of protection.”

Education. Nothing to see here, folks. No gold stars. No stars at all. The trouble was, every classroom had a window, and everything Yvon wanted to learn was out there, not in here.

The Army, conscription, was more of the same. It had more fun to offer, but if you refuse to accept the idea of saluting there’s a limit to how far you can go.

So, out. 1964. After all that education, Yvon needed to breathe some clean air. With three friends he headed to Yosemite and, with no money and bare-bones gear, they made the first ever ten-day ascent of the North Wall on El Capitan. (A ten-day ascent means nine nights sleeping tied to the Wall. And it’s called the Wall because, well, Google it.)

He loved to rough it. In his 20s he was spending 200 nights a year sleeping out in his old ex-Army sleeping bag. “You don’t hurt it much by sleeping in it.” (He was past 40 when he first bought a tent). When the money ran out, he famously lived off dented tins of cat food that the stores couldn’t sell, supplemented with forage. Porcupine was often the dish of the day.

His first business was making and selling climbing gear. He taught himself blacksmithing from a book. Then he would salvage huge, high quality steel blades from abandoned farm machinery and drop forge them into pitons that were lighter and stronger than anything you could buy in a store.

As a blacksmith, Chouinard practised Zen: it’s possible to add by taking away. “Where other designers would work to improve the tool’s performance by adding on, we would achieve the same ends by reducing weight and bulk without sacrificing strength or the level of protection.”

When you've forged it yourself, you know you can trust it.

How high do you want to go?

In the word-of-mouth world of serious rock climbers, it only took a single season for Chouinard gear to become legendary. At the end of his third season they were the largest supplier of climbing hardware in the United States. Every major brand wanted to buy him out. He never returned the calls.

But success comes with complications. This was the 70s, the start of the climbing boom. More and more people were out in the mountains. And the more people who went, the more gear got left in the rocks. Increasingly, a lot of it was Chouinard gear. They were, however reluctantly, the brand leader.

Brand leaders tend to react slowly. They have, or feel they have a lot to lose. They worry about taking their audience with them. They talk about ‘migrating’, meaning - wrongly - moving slowly, and ‘evolution not revolution’. Chouinard didn’t.

He immediately stopped production of steel pitons and switched to aluminium ‘chocks’ that aren’t hammered into the rocks but carefully inserted by hand, then removed after use. It’s a European technique that takes skill and finesse but leaves nothing behind. The first Chouinard equipment catalogue, in 1972, opened with a 14 page essay that introduced the concept of chocks. They were talking about a new way for America to climb. “There is a word for it, and the word is clean”.

They knew the climbing community would be sceptical because, well, because climbers are. On a rockface, show always beats tell, so Chouinard and a young friend tackled the Nose on El Capitan with just a pocketful of his new chocks. They scaled the most daunting face in America without leaving any sign that they had ever been there. A perfect climb. Elegance. Finesse. Purity. After that, doing it any other way looked like vandalism.

But success comes with complications. This was the 70s, the start of the climbing boom. More and more people were out in the mountains. And the more people who went, the more gear got left in the rocks. Increasingly, a lot of it was Chouinard gear. They were, however reluctantly, the brand leader.

Brand leaders tend to react slowly. They have, or feel they have a lot to lose. They worry about taking their audience with them. They talk about ‘migrating’, meaning - wrongly - moving slowly, and ‘evolution not revolution’. Chouinard didn’t.

He immediately stopped production of steel pitons and switched to aluminium ‘chocks’ that aren’t hammered into the rocks but carefully inserted by hand, then removed after use. It’s a European technique that takes skill and finesse but leaves nothing behind. The first Chouinard equipment catalogue, in 1972, opened with a 14 page essay that introduced the concept of chocks. They were talking about a new way for America to climb. “There is a word for it, and the word is clean”.

They knew the climbing community would be sceptical because, well, because climbers are. On a rockface, show always beats tell, so Chouinard and a young friend tackled the Nose on El Capitan with just a pocketful of his new chocks. They scaled the most daunting face in America without leaving any sign that they had ever been there. A perfect climb. Elegance. Finesse. Purity. After that, doing it any other way looked like vandalism.

The beauty of simplicity.

They had changed the face of climbing. Overnight, the piton was history and the chocks business was pumping to keep up with demand.

Not long after, and almost by accident, Yvon Chouinard became aware of clothes. On a climbing trip to Scotland, a rugby shirt caught his eye. Rubber buttons. Genius! Why does anyone make them with anything else? Plus a double-woven collar that’s strong enough to drag a 16 stone man across a field of mud. Everybody needs one of these. And flipped up, it saves your neck from ropes and hardware.

He had learned that the right clothes could be useful. Shortly after, another breakthrough: clothes could enhance the wearer’s appearance. Who knew?

“In the early 80s all outdoor products were full military. Forest green or rust. Some went full scale camel - I don’t know what these people were hiding from. We’d range the Patagonia line in vivid colour. Cobalt, teal, French red, mango and iced mocha. Rugged clothing moved beyond bland looking to blasphemous. The stuff looked like fun, but it was made from technical fabrics that could really perform.”

It worked. “From the mid 80s to 90 sales grew from $20 million to $100 million. We kept all the money in the company. We never took anything out.”

Not long after, and almost by accident, Yvon Chouinard became aware of clothes. On a climbing trip to Scotland, a rugby shirt caught his eye. Rubber buttons. Genius! Why does anyone make them with anything else? Plus a double-woven collar that’s strong enough to drag a 16 stone man across a field of mud. Everybody needs one of these. And flipped up, it saves your neck from ropes and hardware.

He had learned that the right clothes could be useful. Shortly after, another breakthrough: clothes could enhance the wearer’s appearance. Who knew?

“In the early 80s all outdoor products were full military. Forest green or rust. Some went full scale camel - I don’t know what these people were hiding from. We’d range the Patagonia line in vivid colour. Cobalt, teal, French red, mango and iced mocha. Rugged clothing moved beyond bland looking to blasphemous. The stuff looked like fun, but it was made from technical fabrics that could really perform.”

It worked. “From the mid 80s to 90 sales grew from $20 million to $100 million. We kept all the money in the company. We never took anything out.”

Stretch out.

Reach out.

Watch out. (Sorry, friend.)

Success brings complications, but it doesn’t have to bring compromises. “We kept our cultural values as we grew. We still came to work on the balls of our feet. Although we are now an ‘apparel’ brand, anyone could dress however they wanted. When the waves were up there were big gaps in our ranks. Including me.”

Chouinard still has the ethos that was hammered into him in these hours over the anvil: to make a high quality product is to show respect and responsibility to the customer and user.

Mission statement: make the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, and use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.

“Our branding efforts are simple: tell people who we are.”

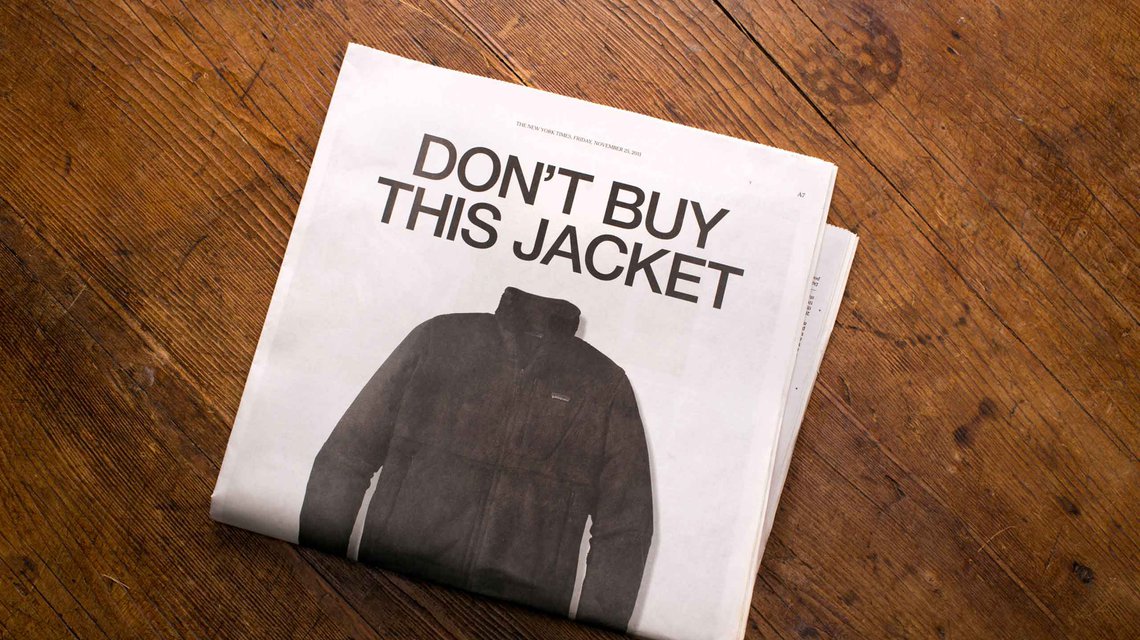

On Black Friday 2011, amongst all the Sale ads and deals, Patagonia ran one of the most famous press ads of our time:

“DON’T BUY THIS JACKET”

First line of copy:

“It’s time for us as a company to address the issue of consumerism head on.”

And then they laid out the story.

Chouinard still has the ethos that was hammered into him in these hours over the anvil: to make a high quality product is to show respect and responsibility to the customer and user.

Mission statement: make the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, and use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.

“Our branding efforts are simple: tell people who we are.”

On Black Friday 2011, amongst all the Sale ads and deals, Patagonia ran one of the most famous press ads of our time:

“DON’T BUY THIS JACKET”

First line of copy:

“It’s time for us as a company to address the issue of consumerism head on.”

And then they laid out the story.

The ad that didn't sell.

Change can start with just a needle and thread. Repair is a radical act. Replacement is king.

Repair, re-sell or pass it in.

Patagonia were the first outdoor brand to offer a complete repair service. The workshop in Reno did more than 40,000 individual repairs in its first year. They were doing vintage when it was still a term used to describe wine.

They were the first, thirty years ago, to reclaim their polyester from plastic water bottles.

They committed to organic cotton in 1996.

More than any sales figure or product line, Patagonia is proud of having given away more than $100 million in cash and in kind donations to grassroots conservation activists. They can point to damage that has been repaired, rivers restored and listed as wild and scenic, and parks and wilderness areas created.

Repair, re-sell or pass it in.

Patagonia were the first outdoor brand to offer a complete repair service. The workshop in Reno did more than 40,000 individual repairs in its first year. They were doing vintage when it was still a term used to describe wine.

They were the first, thirty years ago, to reclaim their polyester from plastic water bottles.

They committed to organic cotton in 1996.

More than any sales figure or product line, Patagonia is proud of having given away more than $100 million in cash and in kind donations to grassroots conservation activists. They can point to damage that has been repaired, rivers restored and listed as wild and scenic, and parks and wilderness areas created.

You wear them, we fix them.

First you build it, then you give it away.

In late 2022, Chouinard, with his wife and adult children, transferred their ownership of Patagonia, worth about $3 billion, to a specially designed trust. All of the company’s future profits will be used to combat climate change.

“If you want to die the richest man, keep investing. Don’t spend anything. Don’t have a good time. Don’t get to know yourself. Don’t give anything away. Keep it all. Die as rich as you can. But you know what? There’s no pocket on that last shirt.”

If there is the key to the story of Patagonia, it lies in the great outdoors. Chouinard is an outdoor man. When he sees a danger, he immediately responds. He reacts like his life depends on it. It’s a surfer’s response. A climber’s.

We could all learn from that. As governments, corporations and individuals we can all see the clear and present danger in the climate crisis. But our responses are as slow and cumbersome as - this metaphor is not accidental - an oil tanker. We have to do better than this. We have to do better.

And we can’t say we didn’t have someone to show us how.

In late 2022, Chouinard, with his wife and adult children, transferred their ownership of Patagonia, worth about $3 billion, to a specially designed trust. All of the company’s future profits will be used to combat climate change.

“If you want to die the richest man, keep investing. Don’t spend anything. Don’t have a good time. Don’t get to know yourself. Don’t give anything away. Keep it all. Die as rich as you can. But you know what? There’s no pocket on that last shirt.”

If there is the key to the story of Patagonia, it lies in the great outdoors. Chouinard is an outdoor man. When he sees a danger, he immediately responds. He reacts like his life depends on it. It’s a surfer’s response. A climber’s.

We could all learn from that. As governments, corporations and individuals we can all see the clear and present danger in the climate crisis. But our responses are as slow and cumbersome as - this metaphor is not accidental - an oil tanker. We have to do better than this. We have to do better.

And we can’t say we didn’t have someone to show us how.

Still waiting for that perfect wave...

Featured stories

See all of our stories