→

Scroll to discover more

The story of Penguin

Pick up a Penguin

When you read a paperback on the train, then slip the book into your pocket with a corner turned down to mark your place, you are paying unconscious homage to a quirky English publisher called Allen Lane.

The train is an important part of this homage because it was in Ipswich Railway station that Allen Lane came up with the idea of Penguin Books. He was escaping from a weekend spent with Agatha Christie and her husband, so he was probably desperate for a good read.

Although, as a proper English gentleman (In a film he would be played by Colin Firth), he hadn’t the faintest idea what marketing was - and would no doubt have despised it had he known - Lane was an instinctive marketing genius. He just made it up as he went along. And a jolly fine job he made of it too.

The train is an important part of this homage because it was in Ipswich Railway station that Allen Lane came up with the idea of Penguin Books. He was escaping from a weekend spent with Agatha Christie and her husband, so he was probably desperate for a good read.

Although, as a proper English gentleman (In a film he would be played by Colin Firth), he hadn’t the faintest idea what marketing was - and would no doubt have despised it had he known - Lane was an instinctive marketing genius. He just made it up as he went along. And a jolly fine job he made of it too.

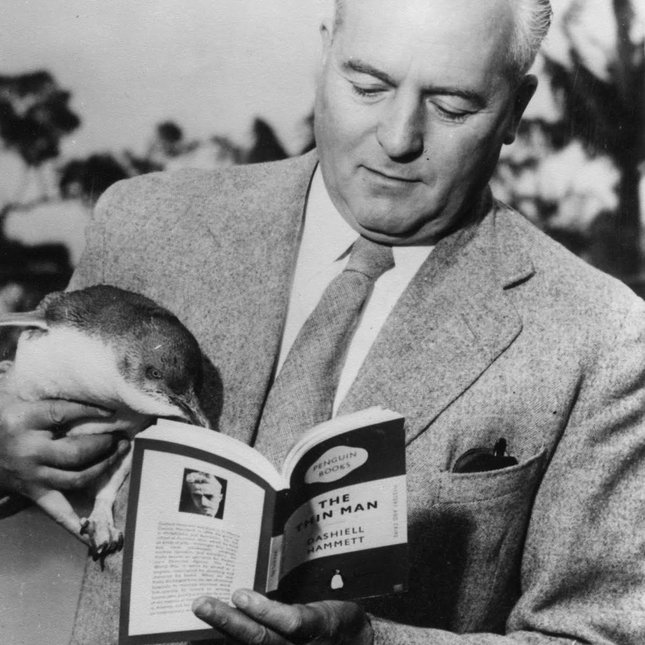

Allen Lane with a penguin

Product.

The paperback book. Contrary to popular belief, Lane didn’t invent this. The format had been around in Europe for a long time but was never taken seriously by English language publishers. Books were stiff and serious things, bound in linen, or even in leather, and sold in bookshops as silent and solemn as churches. Serious people collected them and built them into libraries. They read them in armchairs by the fireside, occasionally pressing the bell for the maid to bring tea. There was probably a pipe involved, maybe even a glass of sherry.

Lane’s idea was to create “cheap, well-designed quality books for the mass market”. The publishing world flinched like an affronted duchess. To make matters worse, his first order was for 63,000 books from, horror of horrors, Woolworth’s. That single transaction financed the start-up. 10 months later, in March 1936, Penguin reached 1 million sales. By the end of the first year it was three million.

The paperback book. Contrary to popular belief, Lane didn’t invent this. The format had been around in Europe for a long time but was never taken seriously by English language publishers. Books were stiff and serious things, bound in linen, or even in leather, and sold in bookshops as silent and solemn as churches. Serious people collected them and built them into libraries. They read them in armchairs by the fireside, occasionally pressing the bell for the maid to bring tea. There was probably a pipe involved, maybe even a glass of sherry.

Lane’s idea was to create “cheap, well-designed quality books for the mass market”. The publishing world flinched like an affronted duchess. To make matters worse, his first order was for 63,000 books from, horror of horrors, Woolworth’s. That single transaction financed the start-up. 10 months later, in March 1936, Penguin reached 1 million sales. By the end of the first year it was three million.

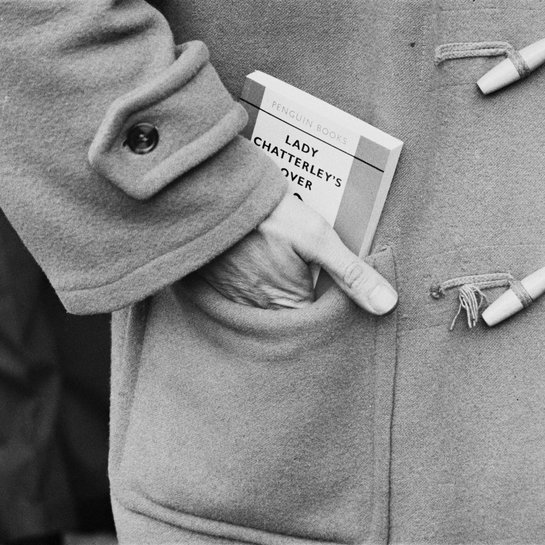

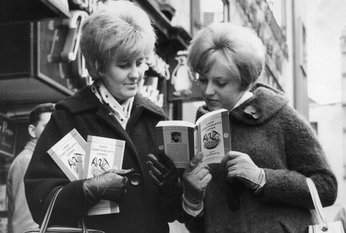

Penguin books are conveniently pocket-sized

Price.

Lane’s pricing strategy gained in efficiency what it may have lacked in sophistication. He reckoned a book should cost the same as a packet of fags. Cigs in one pocket, book in the other. Now, where’s that train?

Place.

This was where Lane really shone. He created freestanding wire display stands that could be placed in any retail environment. He thought that people should be able to buy a book whilst “filling a prescription or waiting for a train.” (There’s that train again) He was interested in people who didn’t have time to go to a specialist bookshop, or who perhaps wouldn’t feel inclined to go to such a place. This radical, but disreputable, new distribution method was a revolution. It was the key to the Woolworth’s deal that made Penguin possible. But. more than that, it also unlocked a whole new way of thinking about what literature was, and how it could be accessed. In its day, it was as disruptive as Amazon.

Lane’s pricing strategy gained in efficiency what it may have lacked in sophistication. He reckoned a book should cost the same as a packet of fags. Cigs in one pocket, book in the other. Now, where’s that train?

Place.

This was where Lane really shone. He created freestanding wire display stands that could be placed in any retail environment. He thought that people should be able to buy a book whilst “filling a prescription or waiting for a train.” (There’s that train again) He was interested in people who didn’t have time to go to a specialist bookshop, or who perhaps wouldn’t feel inclined to go to such a place. This radical, but disreputable, new distribution method was a revolution. It was the key to the Woolworth’s deal that made Penguin possible. But. more than that, it also unlocked a whole new way of thinking about what literature was, and how it could be accessed. In its day, it was as disruptive as Amazon.

A "penguincubator"

He also experimented with vending machines, the first one being on Charing Cross Road. He called them ‘Penguincubators”, so it’s hardly surprising that they didn’t take off.

Although he was from a publishing family (his two co-founders were his brothers), Lane never thought of himself as an intellectual. He left school at 16. He wanted to get on with the practical business of living his life. And his whole success was in delivering books to people who, like himself, had other things to be getting on with.

Promotion.

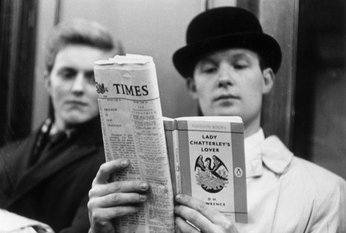

Lane instinctively understood the value of publicity. It was his personal decision to publish the unexpurgated edition of DH Lawrence’s ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’. Lane did it because he wanted to challenge the anachronistic censorship laws. It was a controversial decision: he had to have the book specially printed because his usual printer refused to handle the text. The tone was set by the prosecutor, Mervyn Griffith-Jones QC: “Is it a book you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?” Of all the Penguin authors, only Enid Blyton refused to support Lane. Had the case gone against the company it would probably have been the end of Penguin Books. But, of course, they won and within three weeks two million copies of the book had been sold. It has been in print ever since.

Although he was from a publishing family (his two co-founders were his brothers), Lane never thought of himself as an intellectual. He left school at 16. He wanted to get on with the practical business of living his life. And his whole success was in delivering books to people who, like himself, had other things to be getting on with.

Promotion.

Lane instinctively understood the value of publicity. It was his personal decision to publish the unexpurgated edition of DH Lawrence’s ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’. Lane did it because he wanted to challenge the anachronistic censorship laws. It was a controversial decision: he had to have the book specially printed because his usual printer refused to handle the text. The tone was set by the prosecutor, Mervyn Griffith-Jones QC: “Is it a book you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?” Of all the Penguin authors, only Enid Blyton refused to support Lane. Had the case gone against the company it would probably have been the end of Penguin Books. But, of course, they won and within three weeks two million copies of the book had been sold. It has been in print ever since.

Naming.

Finding a great brand name takes both art and science. Lane used neither. He wanted a name that had “a certain dignified flippancy “. He could have been describing himself (see Colin Firth, above), so it’s perhaps no surprise that it was his secretary who came up with the name Penguin.

A junior associate called Edward Young designed the horizontal bands – orange for Fiction, green for Crime, blue for Biography & Factual (which, as Lane was reported to remark, should have been the same but weren’t always). Young was sent on the bus to London Zoo and came back with some sketches for the logo that is known all over the world.

Brand Architecture.

As the company expanded, new ranges were launched. Lane approached the daunting task of naming the sub brands with his usual cheerful insouciance. He was buying a sandwich in Waterloo Station when he heard a man in the queue wonder aloud “Do you think they have any of these Pelican books?”

Eavesdropping had given Lane the name he needed for his serious, non-fiction, brand. Wikipedia tells us what happened next:

Finding a great brand name takes both art and science. Lane used neither. He wanted a name that had “a certain dignified flippancy “. He could have been describing himself (see Colin Firth, above), so it’s perhaps no surprise that it was his secretary who came up with the name Penguin.

A junior associate called Edward Young designed the horizontal bands – orange for Fiction, green for Crime, blue for Biography & Factual (which, as Lane was reported to remark, should have been the same but weren’t always). Young was sent on the bus to London Zoo and came back with some sketches for the logo that is known all over the world.

Brand Architecture.

As the company expanded, new ranges were launched. Lane approached the daunting task of naming the sub brands with his usual cheerful insouciance. He was buying a sandwich in Waterloo Station when he heard a man in the queue wonder aloud “Do you think they have any of these Pelican books?”

Eavesdropping had given Lane the name he needed for his serious, non-fiction, brand. Wikipedia tells us what happened next:

"Pelican published many of the major intellects of the 20th century. The imprint published books on thousands of subjects from classical music to molecular biology to architecture and became a global phenomenon. The series sold over 250 million copies worldwide over its nearly 50 years. The original books continue to be collected worldwide and prized for their iconic bright blue covers."

In 1939, just four years after the launch of Penguin, Lane met a friend with a briefcase full of litho-print children’s books that he just brought back from the Soviet Union.

Puffin struck Lane as a good name: they are small and fat and wobble about like children.

Mary Poppins, The Hobbit, Doctor Dolittle, The Lion The Witch And The Wardrobe, Watership Down, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, etc. etc. Right from the start Puffin was one of the most important children’s publishers in the world. A position it has never lost.

Lane was committed to design, because “Good design costs no more than bad” (on a personal note, he regularly appeared in Best Dressed lists) He asked Johnathan Cape – the individual, not the company – to recommend the best typographer in the world and got an immediate and unqualified response: Jan Tschichold.

Puffin struck Lane as a good name: they are small and fat and wobble about like children.

Mary Poppins, The Hobbit, Doctor Dolittle, The Lion The Witch And The Wardrobe, Watership Down, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, etc. etc. Right from the start Puffin was one of the most important children’s publishers in the world. A position it has never lost.

Lane was committed to design, because “Good design costs no more than bad” (on a personal note, he regularly appeared in Best Dressed lists) He asked Johnathan Cape – the individual, not the company – to recommend the best typographer in the world and got an immediate and unqualified response: Jan Tschichold.

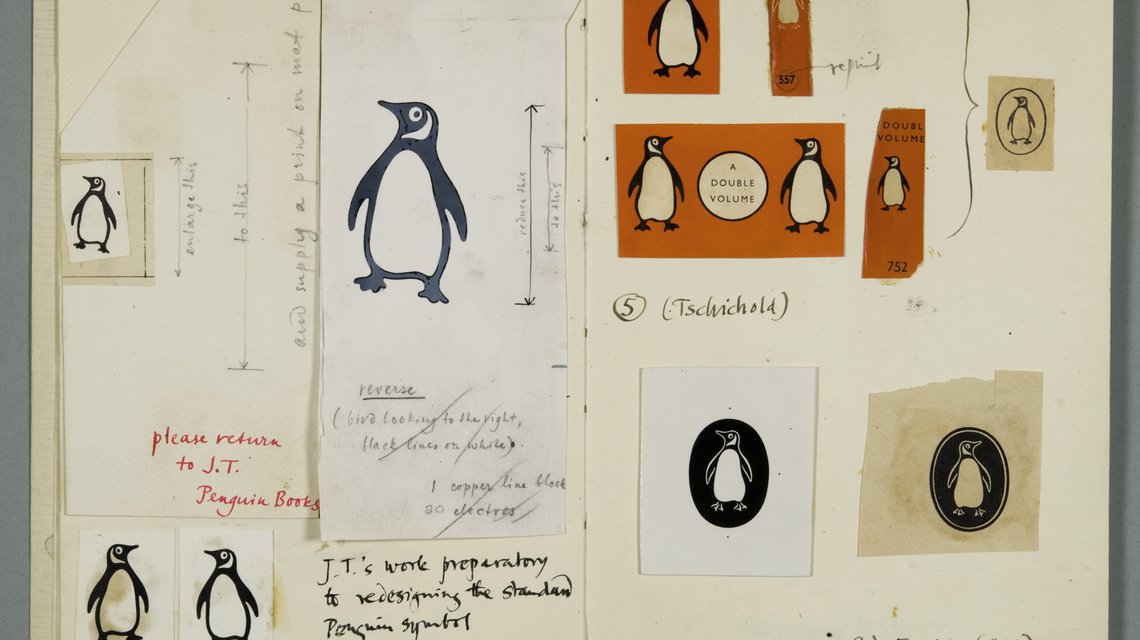

Jan Tschichold's sketches for Penguin

Lane flew to Switzerland where he met a tiny man, rimless glasses and bowtie, in an apartment that was entirely white except for a gloss black floor. Tschichold introduced himself by announcing that Young’s much-loved tubby penguin was ‘deformed’ and must be redrawn immediately: it is Tschichold’s penguin that we know today. He designed the next five hundred books, laying out every line himself and introducing Baskerville, Garamond, Bembo and Caslon. It was said that “No British typographer has his finesse, his obsession or his ruthlessness.” When his perfectionism was challenged, usually by the Accounts Dept, Tschichold would simply forget that he could speak English.

Allen Lane was described by those who knew him as a creative genius who worked on intuition and imagination. Of the many extraordinary things about him, perhaps most surprising is that he absolutely hated cover art. He was reluctantly willing to concede on children’s books, but on anything else all the reader needed was the author’s name and the title.

When, in the early 60s, Lane finally bowed to the inevitable, Abram Games was commissioned, followed by elegantly genteel contributions from Quentin Blake and David Gentleman. But in 1964 the tweed and knitted tie world of publishing was startled when a floral shirt and Afghan waistcoat combo, with velvet bell bottoms and shoulder length permed hair, was proudly hailed as the look of the future. Alan Aldridge had arrived, on his way to The Butterfly Ball, bringing with him a portfolio of psychedelic soft porn that he tipped all over the Penguin list. For the times they were a’changin’.

There is no doubt that Allen Lane loathed the art. But he loved the fuss that it caused. Not to mention the sales.

He finally retired, for the last time, in 1969. His departure was timed, with a characteristically flamboyant flourish, just after Penguin published their 3000th title – James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’

”All I had was a foolish conviction that ordinary people would buy good, well-designed books if they could find them at a reasonable price.”

Last year Penguin sold more than 600 million books and e-books.

Paul Cardwell, The Laughing Saboteur

Allen Lane was described by those who knew him as a creative genius who worked on intuition and imagination. Of the many extraordinary things about him, perhaps most surprising is that he absolutely hated cover art. He was reluctantly willing to concede on children’s books, but on anything else all the reader needed was the author’s name and the title.

When, in the early 60s, Lane finally bowed to the inevitable, Abram Games was commissioned, followed by elegantly genteel contributions from Quentin Blake and David Gentleman. But in 1964 the tweed and knitted tie world of publishing was startled when a floral shirt and Afghan waistcoat combo, with velvet bell bottoms and shoulder length permed hair, was proudly hailed as the look of the future. Alan Aldridge had arrived, on his way to The Butterfly Ball, bringing with him a portfolio of psychedelic soft porn that he tipped all over the Penguin list. For the times they were a’changin’.

There is no doubt that Allen Lane loathed the art. But he loved the fuss that it caused. Not to mention the sales.

He finally retired, for the last time, in 1969. His departure was timed, with a characteristically flamboyant flourish, just after Penguin published their 3000th title – James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’

”All I had was a foolish conviction that ordinary people would buy good, well-designed books if they could find them at a reasonable price.”

Last year Penguin sold more than 600 million books and e-books.

Paul Cardwell, The Laughing Saboteur

Featured stories

See all of our stories