→

Scroll to discover more

The story of Tiffany

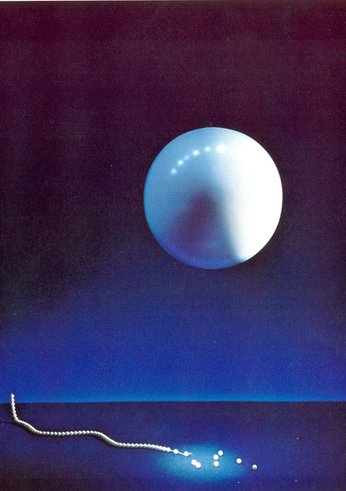

Looking for the end of the rainbow

If ever the romance of a brand was captured by one person and one film, it’s Tiffany and Audrey Hepburn.

She is forever Holly Golightly, the beautiful drifter, out to see the world, who ends up finding the rainbow’s end in the windows of the great Fifth Avenue store.

They never play the Henry Mancini music in the store but everyone who’s ever been there swears that they do.

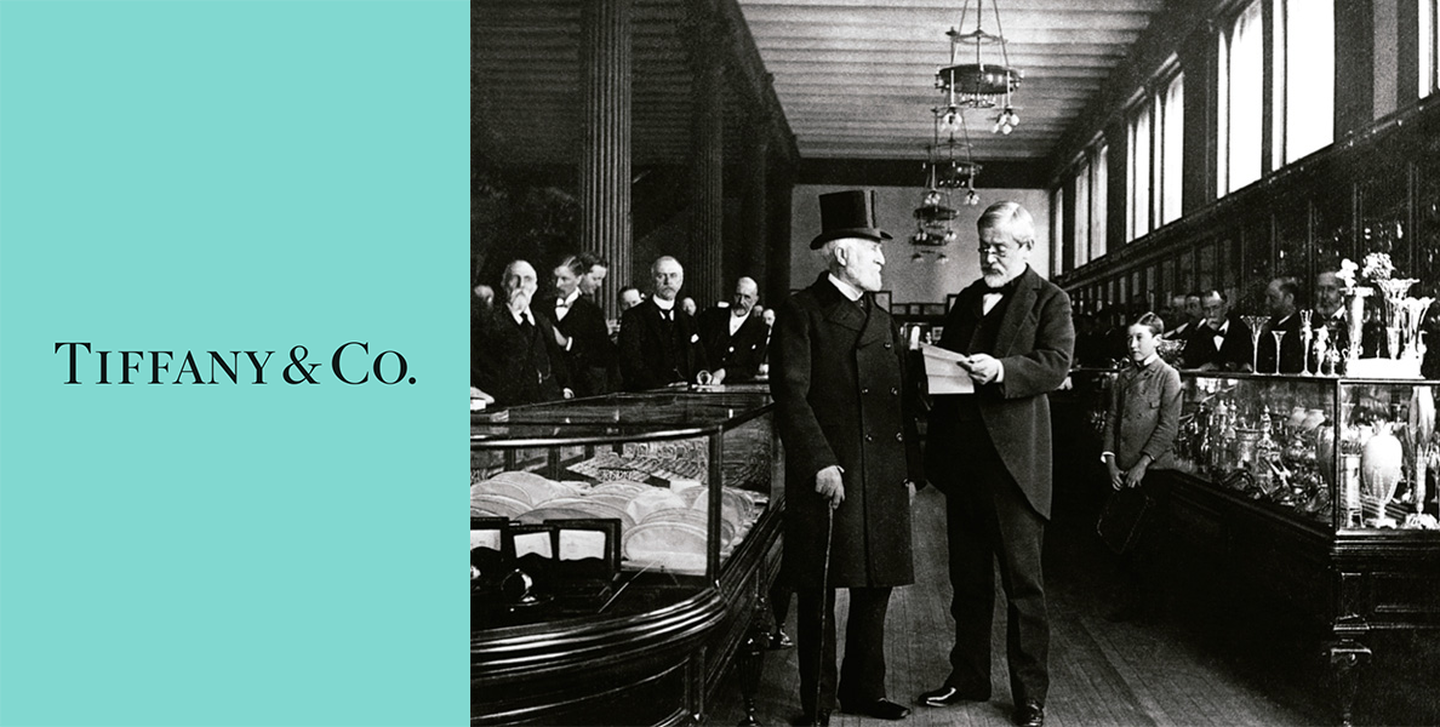

But romance on this scale doesn’t happen by accident, it’s carefully planned. And that plan started way back in 1837 when Charles Louis Tiffany opened a ‘stationery and fancy goods emporium’ on Broadway. It may have been a modest beginning but his ambitions were anything but. His eye for a bargain and his instinct for his customer’s tastes seems to have been infallible. His fancy goods included some very fancy gold and diamond items. Within a few short years his client list included the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Edinburgh, and the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. The firm became the jeweller to Queen Victoria, the Czar and Czarina of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the kings of Belgium, Italy, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Rumania, the Khedive of Egypt, the Shah of Persia, and a whole gaggle of the bejewelled and be-titled.

She is forever Holly Golightly, the beautiful drifter, out to see the world, who ends up finding the rainbow’s end in the windows of the great Fifth Avenue store.

They never play the Henry Mancini music in the store but everyone who’s ever been there swears that they do.

But romance on this scale doesn’t happen by accident, it’s carefully planned. And that plan started way back in 1837 when Charles Louis Tiffany opened a ‘stationery and fancy goods emporium’ on Broadway. It may have been a modest beginning but his ambitions were anything but. His eye for a bargain and his instinct for his customer’s tastes seems to have been infallible. His fancy goods included some very fancy gold and diamond items. Within a few short years his client list included the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Edinburgh, and the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. The firm became the jeweller to Queen Victoria, the Czar and Czarina of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the kings of Belgium, Italy, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Rumania, the Khedive of Egypt, the Shah of Persia, and a whole gaggle of the bejewelled and be-titled.

Romance on this scale doesn’t happen by accident, it’s carefully planned. And that plan started way back in 1837 when Charles Louis Tiffany opened a ‘stationery and fancy goods emporium’ on Broadway. It may have been a modest beginning but his ambitions were anything but.

And because he had them, he also had all of the grand families in the New America. This was The Golden Age, the age of Astors, Vanderbilts, Morgans and Rockefellers. The new Americans wanted to be like the old Europeans – they built houses on Park Avenue that looked like French chateaux. And he knew how to meet that demand. He scoured Europe for one-off unrepeatable items. When the French Republique sold off their crown jewels Tiffany snapped them up then exhibited and sold them, a stone at a time, to his eagerly clamouring audience. He was a genius at self-promotion. When Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated everyone in the audience knew that Mrs Lincoln’s pearls came from Tiffany. When one of the world’s finest fancy yellow diamonds came on the market he bought it and named it the Tiffany Diamond. (He claimed, loudly and often, that it was the biggest yellow ever found. It wasn’t.) The cutting of that stone was covered by every newspaper in America.

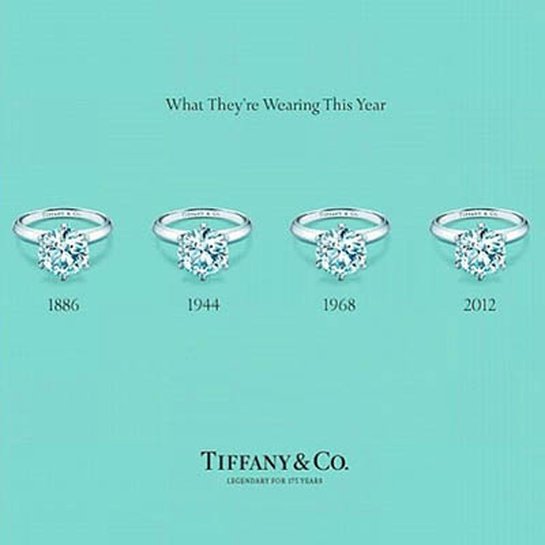

So, long before it became a thing, he knew how to marshal a story. He also knew how to deliver a brand. Everything he sold, everything, left the store in a little blue box. All of his literature, all of his catalogues, advertising, leaflets, posters – blue.

It’s 1878. Tiffany & Co.’s catalogue is now called Blue Book and has its first cover in the robin’s-egg shade that we now know as Tiffany Blue. It was chosen because it was closest to turquoise, which was very fashionable with brides and Charles Lewis Tiffany always had a clear-eyed focus on the wedding business. In real life, romance is never an accident: someone, somewhere, decided to make it happen.

Today, Tiffany Blue is patented and Pantone 1837 Blue (remember that date?) cannot be used without permission.

But for all the huge success and wealth and having made the name world-famous, there still wasn’t a Tiffany look. CLT bought in what he knew he could sell: he followed fashion. It wasn’t until his son took over that the Tiffany name would start to dictate trends and actually set fashion.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was not like his father. He was an artist, not a businessman. His first big decision, in 1902, was not to take over as President or Chairman. Instead, he gave himself the new title of Artistic Director.

He was already a successful designer in his own right and his company, Tiffany Studios, had its own de luxe client list. It was pretty starry: in 1882 President Chester A. Arthur refused to move into the White House until Tiffany had redesigned the interiors.

It’s 1878. Tiffany & Co.’s catalogue is now called Blue Book and has its first cover in the robin’s-egg shade that we now know as Tiffany Blue. It was chosen because it was closest to turquoise, which was very fashionable with brides and Charles Lewis Tiffany always had a clear-eyed focus on the wedding business. In real life, romance is never an accident: someone, somewhere, decided to make it happen.

Today, Tiffany Blue is patented and Pantone 1837 Blue (remember that date?) cannot be used without permission.

But for all the huge success and wealth and having made the name world-famous, there still wasn’t a Tiffany look. CLT bought in what he knew he could sell: he followed fashion. It wasn’t until his son took over that the Tiffany name would start to dictate trends and actually set fashion.

Louis Comfort Tiffany was not like his father. He was an artist, not a businessman. His first big decision, in 1902, was not to take over as President or Chairman. Instead, he gave himself the new title of Artistic Director.

He was already a successful designer in his own right and his company, Tiffany Studios, had its own de luxe client list. It was pretty starry: in 1882 President Chester A. Arthur refused to move into the White House until Tiffany had redesigned the interiors.

It’s 1878. Tiffany & Co.’s catalogue is now called Blue Book and has its first cover in the robin’s-egg shade that we now know as Tiffany Blue. It was chosen because it was closest to turquoise, which was very fashionable with brides and Charles Lewis Tiffany always had a clear-eyed focus on the wedding business.

And he was not just a rich man’s son. He was a real hands-on craftsman and designer. He wasn’t interested in working with gold and diamonds, preferring the textures and tones of semi-precious stones and setting them in silver, bronze and copper. He loved materials and did wonderful work in mosaics, enamels, metalwork, jewellery and ceramics, where he used shimmering, opalescent glazes.

For a man of his time, he was extraordinarily open-minded. He had travelled extensively in Europe, where he was very impressed by William Morris and the Arts & Crafts Movement. On a painting trip to North Africa, he was profoundly influenced by Moorish and Islamic art and architecture – there is always a scent of the exotic and mysterious East in every Tiffany design. In his huge home on Long Island he had a Museum of Native American Art, long before any such thing was openly discussed.

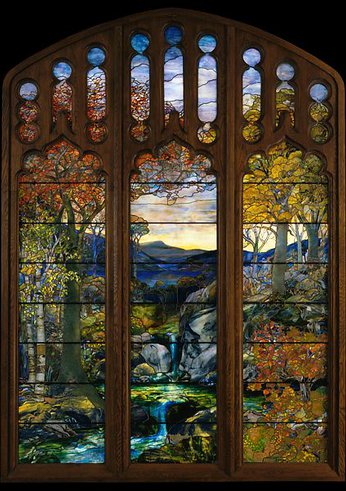

He was most famous for his glass and here again he took a radical approach. For stained glass, he used thin copper foil to join the pieces, instead of the heavy lead channels that Europeans has been using for hundreds of years, which meant that he could work in much finer detail – a technique that found perfect expression is his Art Nouveau style. He upset his craftsmen by bringing in cheap jam jars and bottles because he wanted imperfections and accidental effects, as in Nature, and the art glass makers, trained for perfection (a bubble was a sin), shuddered at the thought. Interestingly, it was the young women in his studio, and there were many of them, who got what he was after and who delivered most of the famous pieces of Tiffany glass.

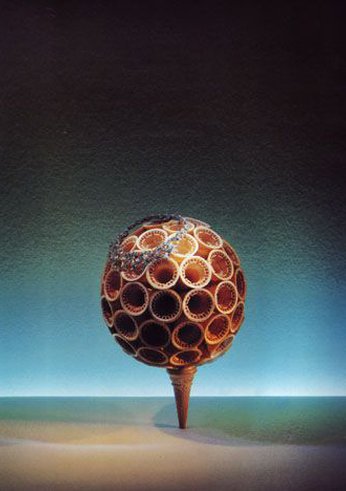

The classic Tiffany lamp is so familiar that we no longer see it at all. But consider this. When Tiffany was working, electricity was new (he actually worked with Thomas Edison - yes, the Thomas Edison - on the first electric lighting for a theatre). People wanted big, bright lights, that turned night into day. They wanted to let the neighbours see how light and bright their homes were. Tiffany lamps didn’t do that, they glowed gently. That was, and still is, the beauty of them.

For a man of his time, he was extraordinarily open-minded. He had travelled extensively in Europe, where he was very impressed by William Morris and the Arts & Crafts Movement. On a painting trip to North Africa, he was profoundly influenced by Moorish and Islamic art and architecture – there is always a scent of the exotic and mysterious East in every Tiffany design. In his huge home on Long Island he had a Museum of Native American Art, long before any such thing was openly discussed.

He was most famous for his glass and here again he took a radical approach. For stained glass, he used thin copper foil to join the pieces, instead of the heavy lead channels that Europeans has been using for hundreds of years, which meant that he could work in much finer detail – a technique that found perfect expression is his Art Nouveau style. He upset his craftsmen by bringing in cheap jam jars and bottles because he wanted imperfections and accidental effects, as in Nature, and the art glass makers, trained for perfection (a bubble was a sin), shuddered at the thought. Interestingly, it was the young women in his studio, and there were many of them, who got what he was after and who delivered most of the famous pieces of Tiffany glass.

The classic Tiffany lamp is so familiar that we no longer see it at all. But consider this. When Tiffany was working, electricity was new (he actually worked with Thomas Edison - yes, the Thomas Edison - on the first electric lighting for a theatre). People wanted big, bright lights, that turned night into day. They wanted to let the neighbours see how light and bright their homes were. Tiffany lamps didn’t do that, they glowed gently. That was, and still is, the beauty of them.

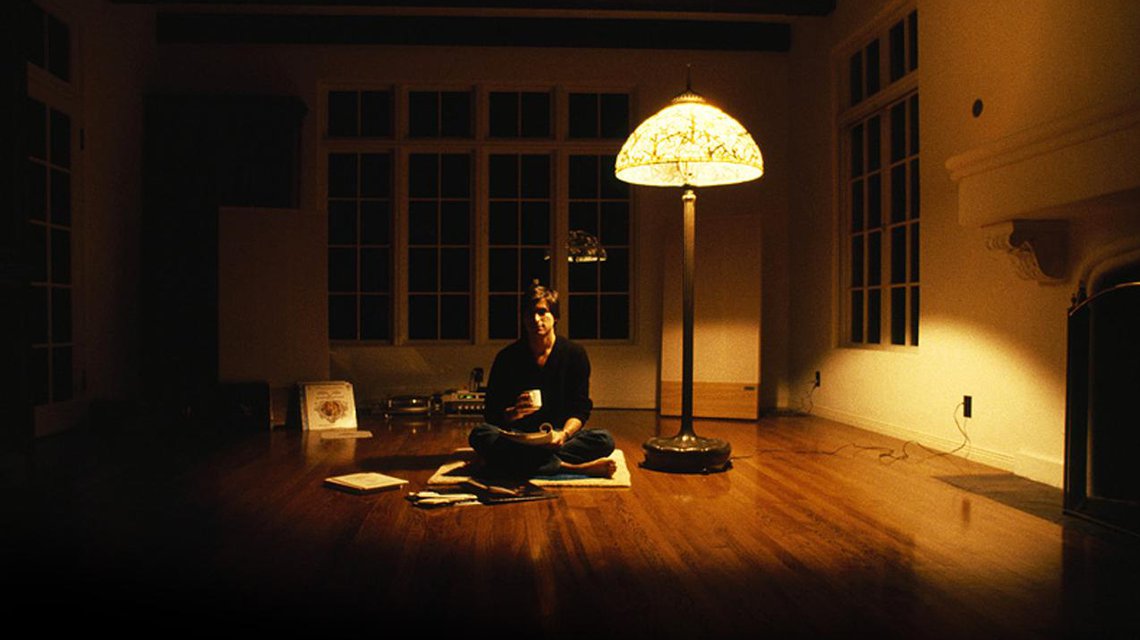

They were haunting, and exotic, and mysterious. Oriental colours flowed mysteriously around elaborate Art Nouveau plant forms. Even the light seemed richer than that from lesser lamps. They were works of art, one of the first great iconic designs of the 20th Century, a classic from the moment they left the bench. (When Steve Jobs lived alone the only furniture he had was a Tiffany lamp and a sound system.)

And so for the first two decades of the new century, the pieces that flowed from the Tiffany workshops astonished the world. Lamps and screens and windows and vases and pavements and fountains were delivered all over America and out across the globe. To homes and palaces and castles and cathedrals.

And then it all went wrong.

The world changed. And style changed with it. The new look was Modernist. Art Deco. Minimalist. The luxurious opulence of Tiffany was as obsolete as a coach and horses.

Tiffany & Co continued: gold and diamonds have never gone out of style, the store was a busy as ever. But by 1930 Louis Comfort Tiffany’s studio was bankrupt and he died, a forgotten and penniless recluse, in 1933. His death certificate said Pneumonia: a more accurate diagnosis would have been Despair.

And so for the first two decades of the new century, the pieces that flowed from the Tiffany workshops astonished the world. Lamps and screens and windows and vases and pavements and fountains were delivered all over America and out across the globe. To homes and palaces and castles and cathedrals.

And then it all went wrong.

The world changed. And style changed with it. The new look was Modernist. Art Deco. Minimalist. The luxurious opulence of Tiffany was as obsolete as a coach and horses.

Tiffany & Co continued: gold and diamonds have never gone out of style, the store was a busy as ever. But by 1930 Louis Comfort Tiffany’s studio was bankrupt and he died, a forgotten and penniless recluse, in 1933. His death certificate said Pneumonia: a more accurate diagnosis would have been Despair.

It’s worth asking: did it have to end this way? Could this man, who was so smart, so worldly, well-travelled and impeccably connected, not have adapted to the new style, not have found a way to make it work? The answer is no, he simply could not. He loved history and culture and allusion and references, all captured in impeccable craftsmanship. In one apartment that he designed for friends he used Japanese, Chinese, Moorish, Viking, Celtic, and Byzantine references. The prevailing theme of the main room was derived from Celtic, Viking, and other medieval sources. For Tiffany the Modernist aesthetic - where a chair can be a tubular chrome frame with a black leather seat - was cold, sterile, dead. He could see no value at all in an object with no history and no obvious connection with the natural world.

But for the Tiffany company, the story was very different. They seemed to surf effortlessly on the waves of change that crashed ashore with every decade of the 20th Century. The shrewd commercial opportunism that had seen the potential in the grand homes of The Gilded Age adapted with feral speed to the new democratisation of money and taste. In 1886 they launched something called a diamond engagement ring. The year on year growth of that business continues to this day. “Every girl loves a ring. And if it comes in a blue box, so much the better.” The Tiffany store saw that the supply of grande dames waiting to be measured for a diamond tiara was dwindling, but the queue for rings could run the length of Fifth.

The dynamic art deco style that Louis Comfort Tiffany so despised became the design philosophy of Manhattan and made New York the architectural capital of the world, with masterpieces like the Chrysler Building and the Rockefeller Centre demanding every bit as much from their craftsmen as earlier styles had. And Tiffany Art Deco was the best of the best: lamps, china, glass, silverware, jewellery. All beautifully crafted and designed.

People changed too. Heritage and history had once been the only qualifications for social success. But a new-minted phenomenon was falling off the end of the production line: celebrities had been invented.

But for the Tiffany company, the story was very different. They seemed to surf effortlessly on the waves of change that crashed ashore with every decade of the 20th Century. The shrewd commercial opportunism that had seen the potential in the grand homes of The Gilded Age adapted with feral speed to the new democratisation of money and taste. In 1886 they launched something called a diamond engagement ring. The year on year growth of that business continues to this day. “Every girl loves a ring. And if it comes in a blue box, so much the better.” The Tiffany store saw that the supply of grande dames waiting to be measured for a diamond tiara was dwindling, but the queue for rings could run the length of Fifth.

The dynamic art deco style that Louis Comfort Tiffany so despised became the design philosophy of Manhattan and made New York the architectural capital of the world, with masterpieces like the Chrysler Building and the Rockefeller Centre demanding every bit as much from their craftsmen as earlier styles had. And Tiffany Art Deco was the best of the best: lamps, china, glass, silverware, jewellery. All beautifully crafted and designed.

People changed too. Heritage and history had once been the only qualifications for social success. But a new-minted phenomenon was falling off the end of the production line: celebrities had been invented.

Tiffany saw this coming. They started, as they always did, at the very top. In 1904 Franklin Delano Roosevelt was surprised to find the engagement ring that he had discretely purchased was on the front of the New York Times. Half a century later Jackie Kennedy was a lot less coy about stepping through the famous doors on Fifth. Today’s regular customers include Anna Wintour and Ellen DeGeneres. Every red carpet is a display stand. Every magazine a window.

This is a brand that sailed into the 20th Century on the crest of a huge wave. One month before that century ended the brand was sold to LVMH for $16.2billion. They must have been doing something right at 727 Fifth.

But what of the man who did so much to create the Tiffany legend? Their first great designer, Louis Comfort Tiffany, who died his lonely death so far from the bright lights of the great city.

Thankfully, this story has a coda. In the 1950s some serious collectors began to retrieve his work from attics and basements. When it’s shown to the public the response is overwhelming. Critical studies follow and it’s not long before the breadth and depth of his contribution is recognised. He is now seen as one of the great American designers. So many of the things that we strive for today are the things that he was practicing. Openness to different cultures, respect for materials, innovative techniques, understanding of history.

But, above all, make it beautiful.

This is a brand that sailed into the 20th Century on the crest of a huge wave. One month before that century ended the brand was sold to LVMH for $16.2billion. They must have been doing something right at 727 Fifth.

But what of the man who did so much to create the Tiffany legend? Their first great designer, Louis Comfort Tiffany, who died his lonely death so far from the bright lights of the great city.

Thankfully, this story has a coda. In the 1950s some serious collectors began to retrieve his work from attics and basements. When it’s shown to the public the response is overwhelming. Critical studies follow and it’s not long before the breadth and depth of his contribution is recognised. He is now seen as one of the great American designers. So many of the things that we strive for today are the things that he was practicing. Openness to different cultures, respect for materials, innovative techniques, understanding of history.

But, above all, make it beautiful.

The life of the great designer is celebrated in an elegant biography, “The Art Of Louis Comfort Tiffany” by Vivienne Couldrey (Full disclosure: the mother of The Lyrical Saboteur, Alan Couldrey. We haven’t yet seen Alan in full Tiffany regalia, but we live in hope.)

Paul Cardwell, The Laughing Saboteur

Paul Cardwell, The Laughing Saboteur

Featured stories

See all of our stories